Passivhaus is a building standard and an important one. In 2019, the World Green Building Council found that buildings are responsible for 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions: 28% from operational emissions, from the energy needed to heat, cool and power them, and the remaining 11% from materials and construction.

Passivhaus is a tried and tested solution for reducing operational energy, backed by over 30 years of international evidence. It gives a range of proven approaches to delivering net-zero-ready new and existing buildings, optimised for occupant health and wellbeing and a decarbonised grid. Passivhaus buildings provide a high level of occupant comfort using very little energy for heating and cooling.

The first Passivhaus prototype was built in Germany in 1992 and is still performing today. Although it is predominantly associated with housing, Passivhaus has been applied to several building types. In the UK Passivhaus design can be found in schools, offices, archives and a leisure centre. Published in 2019, Passivhaus Social: Maximising Benefits, Minimising Costs, reported that there were over 65,000 certified buildings across the globe.

Passivhaus buildings can offer several long-term advantages to the occupier:

Affordability

Passivhaus, by its very design requires less energy to heat the home which is one factor that could address fuel poverty.

Much has been debated about Passivhaus-designed homes reducing building heating demand by 90% when compared to an average home, but the general agreed outcome is that substantially less energy is being consumed within the home when compared to a similar non-Passivhaus home. Saving on energy bills improves the quality of life and means more available funds for occupiers.

A Passivhaus building is not just more affordable to operate, it can also offer lower maintenance costs, which has proven to be a good way for social housing providers to guarantee affordable homes.

Reduced rent arrears

By incurring drastically reduced energy bills, residents can afford to live comfortably, leading to an improved customer experience, which has been found to reduce rent arrears. Additionally, as awareness of Passivhaus design increases it is seen as an attractive marker which can make void periods less frequent.

Increased wellness and healthy homes

Recently, there has been much media coverage focusing on mould and condensation in social housing and its contribution to occupants’ severe ill health. In 2020, a coroner found that toddler Awaab Ishak tragically died from a respiratory condition caused by exposure to mould in his home.

Passivhaus-designed homes have a lack of draughts, cold spots, mould and condensation and create comfortable temperatures and clean internal environments throughout the seasons. The continuous fresh clean air provided by the ventilation system, known as Mechanical Ventilation and Heat Recovery or MVHR provides excellent indoor air quality. Contrary to popular belief, windows in Passivhaus-designed homes can be opened and this is encouraged from a health and well-being perspective.

What are the challenges to Passivhaus?

Although there are many benefits, there are several challenges to delivering a Passivhaus building. When compared to building techniques developed over centuries, Passivhaus concepts are relatively new, and as such it can be difficult to get an experienced contractor and design team on board. Both need to thoroughly understand the Passivhaus concepts.

Understandably, costs can be a concern, largely an uplift in capital expenditure. However, experience has shown that the increase in costs associated with applying the standard can be mitigated as long as the principles drive the design from the very start.

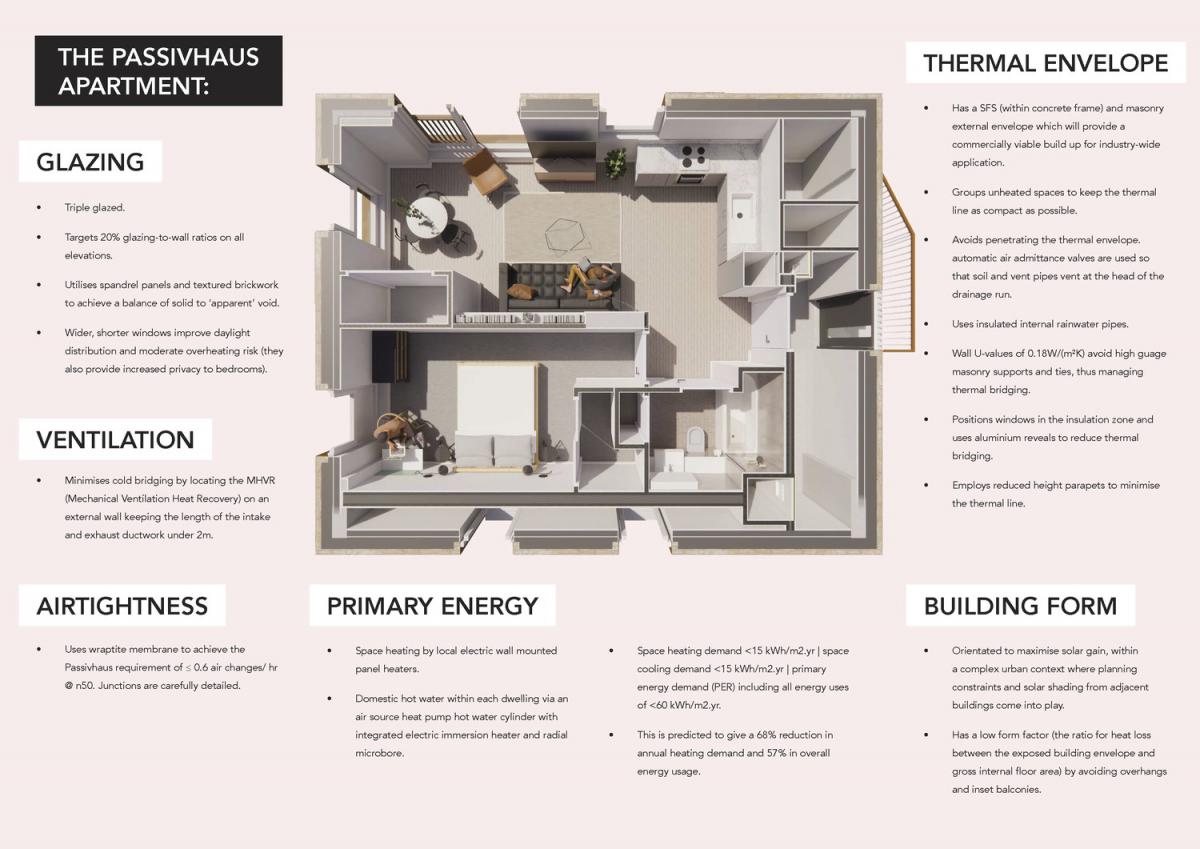

To achieve Passivhaus standards within a budget, it is reasonable to expect cost savings must be sought from elsewhere. An experienced team will create a compact build form and simplify the architectural detailing, thermal and airtightness. This means that it will be easier to meet the stringent airtightness requirements and that most of the heat demand is met by internal heat gains from people and equipment. As a result, the heating plant is far smaller, and the cost savings can be spent on triple glazing, openable windows and highly efficient ventilation systems.

There are additional costs due to the associated certification and quality assurance process. However, this has its benefits to the occupier as this ensures that the project is built as designed with little or no gap in performance. For example, in a traditional building moisture issues often take several years to come to light, and then at that point can be expensive to repair. In addition, the quality of components (eg windows) is likely to be much higher in a Passivhaus as the thermal conductivity and airtightness properties will need to meet a high standard. The overall result is that these components will last longer than inferior alternatives which will reduce through-life costs.

There are key design elements to consider, for example the around the windows. Passivhaus principles suggest that the best design approach would be to have wider and shorter windows, which are sized to balance heat loss and gain. This would improve the daylight distribution in the rooms, and as it’s typically easier to shade it will result in moderating the overheating risk. The challenge can be that this optimal approach may result in a window design that may not sit well in its local context and may seem inconsistent with neighbouring buildings. Also, the windows can appear ungenerous and unappealing to the prospective occupier.

Balconies need careful consideration. The thermal envelope of the building should be as simple as possible to reduce the exposed surface area for heat loss and simplify construction junctions, therefore inset balconies should be avoided if possible. Cantilevered balconies need careful design to reduce thermal bridges. Thermal bridges, which are often referred to as cold bridges, are weak points or areas in the building envelope which allow heat to pass through more easily. The cantilevered structure needs to be thermally isolated from the main frame. An independent balcony structure is preferable but will usually require tying back to the building. A Juliette balcony fixed into curtain walling can provide an alternative. Although these do not provide a usable outdoor space like traditional balconies, they still create a strong connection to the outside and make the interior feel more spacious.

Understandably, costs can be a concern, largely an uplift in capital expenditure. However, experience has shown that the increase in costs associated with applying the standard can be mitigated as long as the principles drive the design from the very start.

Buttress’ Passivhaus experience

Working for client, the English Cities Fund, Buttress has been developing one of the UK’s largest residential Passivhaus schemes in Salford, Greater Manchester.

Greenhaus consists of two blocks; six and eight stories high, which form an L-shape that contains a public square. Overall, the scheme provides 96 units for affordable rent, with a mix of one and two-bed dwellings and four wheelchair-adaptable apartments on the ground Floor. Salford housing provider Salix Homes will manage the scheme.

The scheme utilises SFS (steel framing system) in its structural external envelope which is relatively new in Passivhaus design. SFS has a far quicker installation, than the concrete block used on previously certified apartment schemes in the UK. It imposes less weight on the main structure and can be used in conjunction with mast climbers.

Following on from the success and experience of Greenhaus, plans were submitted for a nearby development to Greenhaus called Peru Street for the same client. It consists of 100 high-quality, affordable, sustainable, one and two-bedroomed Passivhaus apartments within a part five and part six-story building.

Passivhaus starter points

Achieving the Passivhaus standard in the UK involves accurate design modelling using the Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP)

The PHPP is an all-in-one design, verification and certification tool produced by the Passivhaus Institute. It is used from very early in the design process to build up a useful interactive understanding of the design. Initially, only limited information is entered into the PHPP, aligned with the level of design development. During the design process, options can be tested and checked to see instantly what the results on the performance will be.

Once the design is relatively stable, further detail is entered into the PHPP, developing a more granular picture of how the building will perform. At this stage, various aspects of the design can be tested in more detail. Testing elements can lead to an optimised solution for both the design aspirations and building performance. The architect or designer can understand from the PHPP which aspects of the design have the most impact on the performance and therefore, make intelligent choices.

Buttress has produced a guide to starting to think about putting Passivhaus into Practice

Whilst there are many sustainable accreditations in the built environment sector, Passivhaus is the gold standard and its adoption will bring about a host of benefits for the occupier. There may be challenges to introducing this approach, but the benefits will outweigh the difficulties in bringing real long-term solutions to reaching net zero and housing affordability.

Alison Haigh

Alison is an associate at Buttress with over 20 years of experience in the profession, specialising in the design and delivery of major residential projects.

James Lewis

James is an experienced Architect with a range of commercial experience including significant workplace and residential schemes.