The 2018 instalment of Historic England’s ‘At Risk’ list - the annual snapshot of the health of England’s heritage assets - revealed that more than 900 buildings listed were places of worship, representing almost a fifth of all buildings on the register.

There are many reasons why places of worship experience a decline. In some cases, falling congregation numbers means that the church loses its original purpose. In others, the cost of maintaining the building exceeds the amount of funding available to the parish.

Faith buildings by their very nature are intrinsically linked to the community. They have provided a backdrop for christenings, weddings and funerals, they contain generations of memories, and can be representative of an area’s cultural, social and religious heritage. They are anchor points for a community’s sense of place.

As a result, adapting the space not only needs to respect the building’s architectural values, but it should also reflect its position as an important emblem for the community. In identifying a future use, careful consideration needs to be made as to whether the new use is viable and appropriate to both the building and the community it serves.

There is a broad range of potential uses for redundant faith buildings, and they can include community, residential, leisure and commercial use. However, regardless of the building’s future use, it is important that the potential use should be sensitive and appropriate to the historic character of the building.

Any proposals should be informed by a deep understanding of the building’s past, and a clear vision of how its historic and liturgical features can be sensitively retained within its new function.

A commonality with most places of worship is the sense of volume within the space and it is important to retain, where possible, this significant characteristic. This maintains the building’s intrinsic architectural values and ensures that the way in which the building was originally experienced can continue to be read through its new use.

When working with buildings of a church’s scale, it is often difficult to generate a viable use, without sub-division. However, innovative approaches can positively make use of this significance.

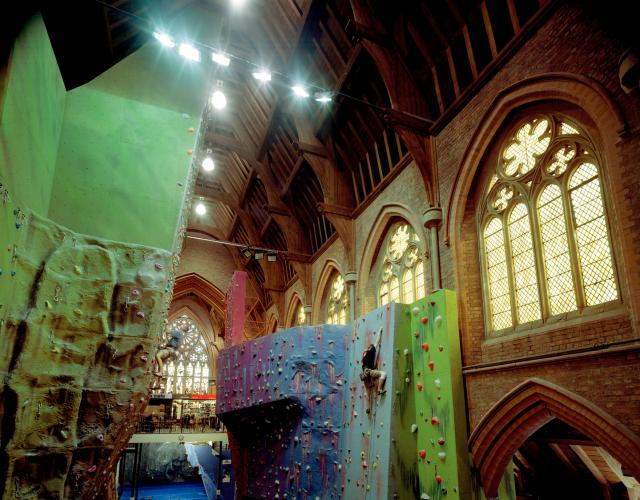

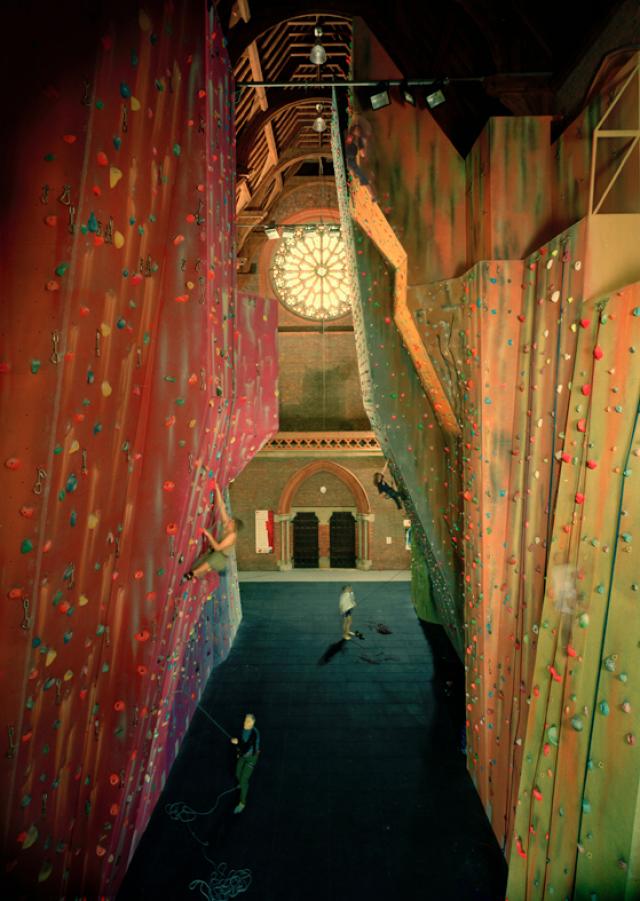

For example, the adaptation of St Benedict’s Church Ardwick, is an example of how this can be done successfully. The Grade II listed church was built in 1880 but closed in December 2002 due to declining congregation numbers. Buttress was appointed in 2003 to convert the building into a climbing centre.

The space is defined by the voluminous nave, exploited by towering climbing walls which cantilever into its height, mimicking the roof structure and providing the climbers with challenging overhangs and diverse routes.

By concentrating on conserving and utilising the church's existing architectural forms and styles while adapting to a new use, neither the new use nor the existing fabric of the church has been inhibited or overwhelmed by the design response, instead, they sit comfortably together. This has given the building a sustainable new use, secured its future, while supporting local regeneration.

Similarly, at St Peters Church, a Grade II listed deconsecrated Italianate-style church in the heart of Ancoats conservation area, the building’s volume has been exploited to allow the church to be converted into a new rehearsal venue for the Hallé Orchestra.

To enable this, a series of ‘Sound Sails’ has been installed within the church using pulleys, with no fixings to the structure, so the building was left entirely as it was found whilst adapting its original acoustics to its new use.

Here, the spatial qualities and the church’s interiors support its new use as a rehearsal space by providing a wide, open space for music groups to congregate and an acoustic environment tuned to the orchestra’s requirements.

In cases where retention of the space’s volume cannot be viably accommodated, sensitive solutions can be found by building in good quality repair that retains surviving features, as was the case with the restoration of the Unitarian Chapel (also known as the Welsh Baptist Chapel) on Upper Brook Street in Manchester.

Designed by eminent Victorian architect, Sir Charles Barry, over the years the building had fallen out of use and by 2006, it was partially demolished due to safety concerns. Buttress was appointed to reinstate the church’s original form and convert the site into student accommodation.

Due to the dilapidated state of the chapel’s interior, much of the internal features were unable to be retained. However, some key elements were able to be saved. Timbers from the chapel balcony, for example, have been used to create a new front desk, whilst the vaulted springers remain in-situ to become a feature within the rooms.

The apartments have been inserted into the body of the church using a steel frame which has been designed to ensure that it does not clash with the historic fabric.

The finished project has both rescued a vulnerable heritage asset and created new accommodation for students looking for high-quality housing in a city centre location.

Although redundant places of worship may no longer serve a religious purpose, they continue to make a positive aesthetic, communal and perhaps spiritual contribution to the places in which they are found. Re-using these buildings whilst preserving their historic significance may appear to be a challenging undertaking, but by respecting the past and combining this with thoughtfully designed interventions, positive new uses can be found.